- Home

- Margaret Baumann

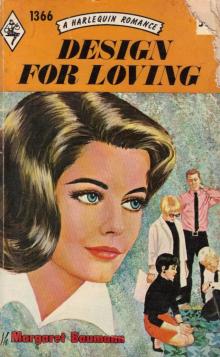

Margaret Baumann - Design for Loving (1970)

Margaret Baumann - Design for Loving (1970) Read online

Margaret Baumann - Design for Loving

When Neil Haslam became principal of the Technical and Art institute in a remote country town, he found the place grinding to a standstill, and started a one-man revolution to reverse the process. Neil let it be known that the whole staff had not an original idea among the, but there was one member of the staff who made him think again — in more ways than one.

CHAPTER ONE

A wind had risen, roughly tearing the mist apart, and the lights of the valley sprang out all of a sudden with the splendour of a fireworks display: the railway plotted out in reds and greens, the wet highroad a glistening black serpent patterned with blurs of orange. Along the river bank a row of cottage windows made squares of pink and yellow, and there was a flicker of yellow, too, from the abbey where a choir practice must be in progress. The night watchman doing his rounds with an electric torch down at the wire works became a capricious will o' the wisp dancing through some enchanted woodland. And then there was the carpet mill, lording it astride the river, tier upon tier of lights turning the dark satanic pile into an Aladdin's palace for the night shift.

Staring down upon all this beauty from his office in a corner of the old building on the hill, Neil Haslam reminded himself ruefully that lights meant people: people in a rut, fortified against him in their narrowness and indifference. Precisely at this moment the truth emerged blindingly from the vague misgivings of the past weeks. Roxley was the mistake of his lifetime.

He turned his back on the lights and sat down at his littered desk. I must have been out of my mind, he thought. He said it aloud, savagely. 'Out of my mind. Stark raving bonkers.'

The door opened a crack and a mini-girl in a black leather coat, handbag over her arm, stood staring at him through her fringe.

'Did you call, Mr. Haslam?'

'I did not. But while you're here, Betty, where in heaven's name is the urgent memo that came this morning from County Hall?'

'I put it on top of the pile, of course.' This with reproach. 'And I'm not really here, Mr. Haslam, if you know what I mean. My hours are ten till six, when Percy takes over. And Mr. Cragill always used to let me leave promptly because my mum worries so. I've only stayed late these past three weeks till you got in the way of things, sort of.'

'I know, Betty, I know. And I'm grateful.'

Betty was a graduate of Miss Gorple's shorthand and typing course and had stayed on, sort of, not through any outstanding ability as a secretary but because she 'liked working with students'. Neil had been warned that the staff turnover in the Technical College office was alarming. They tended to leave at about eighteen to get married. And so, though there were many things at Roxley which he passionately desired to throw on a bonfire or demolish with gelignite, Betty was part of the status quo to be handled delicately. He corrected all the typing errors himself, and now he let a note of friendly appeal creep into his voice as he said: 'If you'd just think hard, Betty. On top of the pile, you said ?'

They rummaged together through the mountainous stacks of papers. It was like some crazy game of cards with everyone cheating.

'Can this be it?' sudden hope lifting his voice. 'Form T(X)45.'

'No, Mr. Haslam. That's the instructions about the certificate tests next Easter. T for technical and X for exams.'

'And this is only September,' said Neil, appalled. He rubbed a distracted hand through his hair, thick-springing and dark. 'Next Easter! God help me, they can't call that urgent!'

'Have you looked in the drawer?' said Betty.

He looked in the drawer. There was the County Hall memo, marked urgent in red, on top of a lot of other papers.

'You see?' Betty gave him a pitying smile and began to ooze out backwards through the crack in the door, rather like the Cheshire Cat. Just before the door closed, she remembered something. 'Oh, Mr. Topliss rang up at seven o'clock. They're short-staffed on the Gazette and the editor has sent him to report on a political meeting. Of course, it was too late to let his class know.'

Neil did mental acrobatics. 'Topliss. Gazette. Freelance writing. You sent the class home?'

'Oh, no, we never do that!' Behind the fringe Betty's eyes were very wide. 'They're reading one another's stories aloud and having a whale of a time. The trouble is, the class will get an attendance mark and Mr. Topliss won't. It's very awkward about salary.'

'It will knock County Hall for six,' agreed Neil drily. 'Look, the situation is preposterous. When we are let down like this at the last moment, there should be a deputy we can reach by telephone. Yes, a complete dossier of deputies. I'm new to evening classes, but surely every institute must have a system? The thing is plain common sense.'

Betty gave a little cough. 'If a class was left without a teacher, Mr. Cragill would go along and chat them up. He'd set them a bit of work to do and mark the register. That straightened everything out nicely.'

Neil said in an awful voice: 'Mr. Cragill is no more. He is retired, abdicated. He is but a shade. Will you get it into your head, girl, that I'm running this place?'

Betty gave an audible gasp. Her eyes popped. She vanished through the crack.

Neil put his head between his hands and groaned. Now she'll think me an ogre. Probably hand in her notice tomorrow. And that'll land me with the typing on top of everything else… This was a day when nothing, but nothing, could go right.

He would have been astonished to hear Betty, as she linked arms with her friend who had been waiting around outside.

'He's fab. How old? Well, thirtyish. Sort of noble and smouldering with secret fires, and terribly, terribly good- looking. If he ever gives me my cards I'll just curl up and die… I mean, after a creep like old Sammy Cragill!'

The urgent memo from County Hall was a reminder that Form T(S/A)12 regarding staff appointments (see salary rates based on qualifications and experience, as set out on Blue Sheet S5) was overdue and should be submitted (in duplicate) by return of post.

Neil could see the urgency. After only three weeks of the new session, some classes were in danger of folding up before County Hall had even given its blessing to the appointments. Only three persons had joined the class on Public Speaking, which washed it off the syllabus immediately, as ten was the minimum for grant. The daytime courses were languishing, too, though he, had toiled mightily to get them off to a good start. The local firms were slow in sending their apprentices for full-time courses or even on day release. Of course, under the Industrial Training Act of 1964 there was no compulsion; but every inducement was offered and he had been enthusiastic at this idea of obtaining an objective report on a youngster's capacity before he was let loose on the shop floor. In the Roxley valley, no one was buying it! As for the non- vocational classes, they weren't even a starter.

The reason had been clearer to Neil since he began going into the classes, making himself inconspicuous in the back row for ten minutes. French, for instance. He had discovered a spinsterish little person droning through an old-fashioned grammar while the students, dumb and disillusioned, scribbled or doodled: a roomful of people keen to rattle off fluent conversational French on their trip abroad next summer. When he saw Miss Frith afterwards and suggested oral tests, she had looked shocked, and she reacted to the words 'language laboratory' as if he had mentioned the Woomera rocket range.

"You see, Mr. Haslam, as the numbers fall off I have to teach three years' French in the one room: put together they make a full class. Mr. Cragill was very helpful. He pointed out that if we stuck to written work, I could keep them all happy and busy at once.'

Samuel Cragill, what you have to answer for! You are a humbug, sir, and a villain. Rage boiling up withi

n, Neil recalled the bland deceptions of that conducted tour in May when he had been short-listed for the post. The classes, Cragill told him, were 'just slackening off for the summer. You know what it is in a country district, my boy.' In fact, under Samuel Cragill's long headship, the Roxley Technical Institute had been run down almost to a standstill. Since he took over the controls at the beginning of September Neil had found muddle, inefficiency and outdated methods in all departments.

And the worst of it was, Samuel Cragill still haunted the place in the spirit and in the flesh. In preparation for retirement, he had shrewdly bought the field behind his house, tipped three tons of rich farm muck thereon and was already growing prize vegetables, shrubs and flowers whose Latin names rolled sonorously off his tongue.

Stark raving bonkers, Neil repeated, this time in despair. Why had he thrown up a senior post in an excellent city school to take on Roxley - Betty, Samuel Cragill and all? First and foremost because of Jennifer. He still couldn't think of her without shock and grief and bitterly wounded pride. Their future together had seemed so secure. Then, when everything fell apart, he had been seized by the compulsion to tear up his roots. He would leave behind the familiar scenes that reminded him constantly, achingly, of her. He would set himself some task that stretched him to his uttermost. Roxley had seemed to offer precisely such a challenge. He had been enticed here by grandiose ideas of the new 'education for leisure', by the apprentice-training schemes, administration on a practical level instead of economic theory. Evening classes had seemed a fair swap for parents' meetings or the sixth form debating society…

He stared at the memo on his desk. By return of post, or else… But not, dear Lord, at this hour of night and after such a punishing day!

The little office was stifling. This huddle of low buildings on the hilltop had been a cottage hospital before it became a centre of learning, and the ghosts lingered. Bare walls with canted corners for the sake of hygiene. Stark corridors, each with its spyhole into what had been the wards. Ramps for stretchers. And everywhere the ancient memories of cabbage and antiseptics. Yes, after ten years. You could scrub away like Lady Macbeth and never be rid of the traces.

He strode across and with a vigorous gesture flung open the window. Away down there among the valley lights, the abbey bell solemnly struck eight, the sound borne towards him on the wind. Another, keener blast of wind and the desk papers were set whirling like a snowstorm.

'Oh, Mr. Principal, how unfortunate!'

It was the clerk, Percy Barrow, with his thinning hair, his long, pouched, sad face like a bloodhound's, and gentle, refined voice.

Neil roared: 'Shut the door, man, and lend me a hand.'

They were down on their knees, scrabbling for papers.

As they built up the piles on the desk again Neil saw with unholy joy that the urgent memo from County Hall had vanished without trace.

Still kneeling, Percy offered him a slip on which a message was neatly written.

'Mrs. Collins phoned. Some friends dropped in and she was unable to attend Embroidery and Design. She'd like Miss Birch to have her apologies. I'll nip across with the message, Mr. Principal, if you don't mind listening for the phone. Miss Birch holds her class in the old path lab, of course.'

Neil thrust the slip of paper in his pocket and stood up, red-faced. 'I'll take it myself.'

He made for the door in a blind rush and escaped to the freedom, to the windy, starry darkness. Out there, with little spears of cold assailing his heated skin and the dry sycamore leaves falling with a sound of tiny machine gunfire, he stood getting his bearings. Three weeks of the Michaelmas term gone and he still hadn't, to his shame, visited every class or even met all his 'casual' staff - what with the interviews and committee meetings and the paper work. He wasn't even very sure of his topography. Embroidery and Design in the old path lab. It was fantastic, farcical.

His mind was suddenly made up. He couldn't stay at Roxley. His school in the city was being reorganized and he might have had a go at the headship of the new sixth form college. Yes, he'd been a fool to let that chance slip. But there were other posts. He'd hand in his resignation at Christmas, and by Easter he'd be free to return to a sane world; decent striving towards some real purpose…

He had to pass an old Army hut and remembered that this was the Joinery Department. Handicrafts. Ha, the magic word leisure! Coffee tables and toast-racks - and, of course, a day course for apprentices if any employer pushed them into it, which hadn't happened yet.

He groped around in the dark till he found the two wooden steps and the door. He walked in. The smell of frying met him. Six lads were seated on stools round a work bench. They wore joiner's aprons and looked absorbed and happy. The instructor, a small elderly man with gnarled hands and the clear skin and bright, alert look carpenters have, was frying sausages over a bunsen burner, and upon the bench were hunks of bread and seven steaming mugs of tea.

Neil stood just inside the door. When he found his voice, he said carefully: 'Mr. Smart.'

The workbench was suddenly deserted and from various corners of the hut came a clamour of sawing, hammering and polishing. Mr. Smart took the frying pan off the bunsen burner and came very slowly across the floor, wiping his hands on his apron. They were shaking visibly. When he came close and raised his head, Neil was appalled to see his eyes swimming with tears.

'If one more student leaves, you'll close the class. And I need the money badly.' That was all. What had appeared wildly comic was all of a sudden a painful little tragedy.

'Look, I've said nothing about closing your class"

'Ten's the minimum. It's a question of grant, I know. Mr. Cragill used to look the other way, but I couldn't hope…' He began to cough like a wheezy bellows. Neil patted him on the back till the paroxysm was over.

'I take it you still have ten on the register, even if they haven't all turned up tonight? And when word of the supper break gets round…' His lips twitched. 'Drink your tea, man. And for goodness' sake don't waste those bangers.'

He went out quickly. Why in heaven's name had he gone blundering in there? But I must. I have a responsibility to my students, to the governors, to County Hall. I can't just look the other way and cook the figures like old Cragill. If Smart really has only six students I'll have to close the class. Damn and blast…

Visit the old path lab and call it a day. God help me, all those weeks till Christmas when I hand in my resignation and I'll be lucky if they let me go after the Easter exams. Form T(X)45. Believe it or not, these people all have to sit for certificates. Easter will be a marathon of exam timetables, reports, form-filling. He was like a man running through a maze, with Time - a grotesque, hard- breathing giant - pounding after him.

Embroidery and Design in the path lab. Monstrous! How the smell of formalin lingered. He fancied it came out at him in waves and that great dark cupboard just behind the door might yet hold unmentionable bits and pieces pickled in spirit. The doorway was narrow and his big shape seemed to fill it. He stood there taking in the fact that it wasn't formalin at all, but the pungent smell of a country hedgerow. A group of women wearing nylon smocks in different colours stood round a table on which were heaped crimson leaves of mountain ash, tawny bracken fronds, rustling ghostly sprays of honesty, long reeds wearing brown velvet caps, great clusters of berries, scarlet hips, the glossy red and black of bryony. They were chattering away like a flock of little parrots as they selected and arranged all this autumn plunder in a big blue pottery jug.

Neil was completely taken by surprise. But the first impression of delight faded. Whatever they were up to, it certainly was not Embroidery and Design. He stood in seething silence. Then all the day's smouldering irritation spurted into flame. He pronounced in a loud, outraged tone: 'Flower people!'

He had startled them effectively and the group opened up with little chirps of surprise. One of them laughed musically.

'Oh, I don't think we really deserve that!' She was a dark-haired girl in

a moss green smock, her face pointed, her skin clear and pale. She came forward with a sudden eagerness that lit up her face. 'Mr. Haslam? I'm Sharon Birch. I wish we'd known you were going to look in on us. We'd have had something ready to show you.'

He glanced at the mess on the table and his jaw tightened. He dug out the slip of paper and thrust it at her.

'Mrs. Collins phoned with apologies for missing the class. But she hasn't really missed very much, has she? Does it not occur to you, Miss Birch, that a student who pays the session's fees to learn Embroidery and Design may well prefer an evening at home with friends if she is offered' - he made one of his fierce gestures towards the table and the blue jug - 'nature study for eight-year- olds?'

Sharon Birch gave a little gasp. Colour came into her face and ebbed again, leaving her shockingly white. The thick lashes made a dark smudge round her eyes so that it wasn't possible to tell their colour, but anger burned there. She said in a clear voice: 'Do you, by any chance, know what you're talking about ?'

One of the students, a middle-aged woman, tittered nervously. Neil was brick-red. He had never been so angry in his life. He stepped back and somehow his shoulder caught the door of the tall cupboard. It flew open and out toppled, not pathological specimens in little jars of spirit, but a quantity of small felt objects crudely adorned with cross-stitch in strident reds and greens. Sharon Birch looked as shocked as if she had witnessed a sudden invasion of black beetles.

Neil studied the felt objects attentively.

'Egg-cosies. And I daresay you have some hot water bottle covers and kettle-holders to show me, Miss Birch? You see, when it comes to junior school work, I really do know what I'm talking about.'

She opened her eyes very wide. And a powerful shock tingled through his body. They were unbelievably blue, almost violet, the exact blue of that jug on the table.

The veil of eyelashes came down again. She said in a small, hurried voice: 'If I could have a word with you in your office tomorrow evening, Mr. Haslam?'

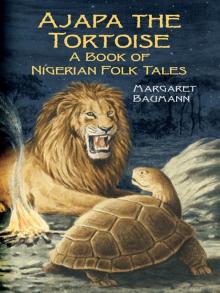

Ajapa the Tortoise

Ajapa the Tortoise Margaret Baumann - Design for Loving (1970)

Margaret Baumann - Design for Loving (1970)